That’s how my afternoon conversation with J. Cole begins. He repeats the question he posed to himself. We’re posted up in the workout room of a parks and recreation facility in Raleigh, NC. I’m fairly sure it’s the room the community center uses for yoga and stretching classes. The kind seniors attend to stay limber and remain social.

Our early morning was spent outdoors with Cole posing various looks for the day’s photo shoot. We’re a small group, less than a dozen of us gathered on the asphalt. At one point I realize I don’t know if it’s due to COVID precautions or Cole’s low-maintenance lifestyle and laid-back demeanor. Probably a mix of both.

In group settings, he’s mostly silent, besides some visible nervousness around the idea of sitting on top of an aged basketball hoop that has seen better days. You know, the kind of hoop that has the cloth net that’s been up so long that it’s fuzzy and frayed—the kind of net that holds onto the ball like a Venus flytrap after a shot is made. “You said you tested this?” he asks the group while trying to get comfortable on the rim. “Yeah?”

And now here we are, just a couple hours later with the day’s shoot wrapped, conversing in a space commonly used to channel calmness, well-being and clarity.

On its face, Cole’s question—Am I going to be doing this forever?—sounds like he’s floating the idea of leaving the rap game. It’s something that circles everyone who does anything from the moment they make their debut. It has a particular significance and status in hip-hop ever since Hov announced his “retirement” from rap in 2003.

If you’re in the NBA, this notion might not be as celebratory. Maybe this thought occurs after you’ve clocked a few years in the League. Maybe after the first time a new rookie outscores you in practice. Or when you notice your legs don’t have the hops they used to. Or while trying to come back from a tough injury. A fearful moment that this is all you’ve ever wanted to do—and maybe all you’ve ever prepared to do—and the trembling juxtaposition that you’re smarter than you’ve ever been, but your skills are declining and your time is dwindling. Maybe.

For Cole, 36, it was nothing close to these moments. The opposite, actually. He reveals that the thought first entered his mind years ago in 2014, following the success of his third studio album, 2014 Forest Hills Drive.

“After [2014] Forest Hills Drive, [that] was the first time I ever got that feeling,” he says. “It was after I got off tour and I could breathe. I was like, Damn.” Cole’s shoulders slouch as he relives the feeling of relief and relaxation. “For the first time, I felt comfortable in a good way. I allowed myself to just chill, watch TV, play video games. Simple shit that ni**as do, but I don’t do. Shit that before I wouldn’t allow myself to do, because it was like, Yo, I got way bigger shit to do, way bigger fish to fry. I wouldn’t even give myself the pass of watching a whole [TV] series.”

Forest Hills Drive had generated his then-greatest wins. Delivered at the tail end of 2014, the 13-track album found J. Cole rapping (and crooning) his ass off—shedding the baggage of past criticisms. It had the fun of albums prior, but its highest moments achieved a thoughtful depth that was audibly cathartic. It was a new way to look at J. Cole.

Cole took to the road with a world tour the following spring, bringing his music directly to his fans in many of the same venues home to NBA franchises. He had reached a coveted higher level. But it was when he returned home that he found the joys of comfort, but also the conflict.

“I gave myself that time,” Cole says. “And with that time came thoughts, very comfortable thoughts of like, Yo, you kind of got to where you always wanted to be. Now what?”

The time spent unwinding from years of forward, perpetual motion opened the door to relaxation—but also reflection and new possibilities. He remembers thinking, “That feels really comfortable. It feels like a viable option. It feels like some shit that would be nice.” He flat out asked himself, “Do you want to stop right here?”

My facial expression must have given signs of my disbelief, because he immediately explained:

“And when I asked that question it was strictly from an ability standpoint, a fulfillment standpoint. Like, Did you max out your skill? Did you max out your abilities or did you leave shit on the table in terms of pushing yourself? And at that time, I remember feeling like, No, no you didn’t. The truth was very clear.”

It was around this time, Cole recalls, that he started writing again, but he was still in break mode. There was no real urgency. He was like a baller in the offseason, stopping by an empty gym to get shots up, putting up a few too many bricks.

“I could tell, sometimes I would pick up the pen and write at that time. And I didn’t really have any real reason. I had just got off tour, there was no rush to do anything. But if I tried to pick up the pen, if I tried to make a beat, the shit would be uninspired.”

Despite having penned his best project the year or so prior, Cole was seeing that his rap form wasn’t delivering in the way he had become accustom to. That his latest creations were flimsy, not meeting his own personal standard. Shit wasn’t hitting the same.

As humans, much of our lives are built around goals: setting goals, pursuing goals, accomplishing them, and then chasing new ones. So driven that we develop laser focus with our mind and our body follows in purposeful motion. But even the most driven can have trouble taking off from the line when their momentum has been broken.

“It was the feeling of analyzing it and being like, What’s going on right now? You’re really uninspired. Why?”

That “Why?” fueled Cole to have an honest conversation with himself. He recounts the inner dialogue.

“OK, here’s the reality. The shit that I just wrote is not even impressing me. That’s the reality. Or the shit I been writing this week, or the shit that I wrote this month, none of it has even moved me at all. Why is that? Oh, OK, well the answer to that question is, clearly, comfort.

“You’re doing things you never did before. You’re sitting around the house. You’re going to play ball every day. You’re watching fucking Narcos. And that’s cool, but this is the inevitable result of not pushing yourself.”

Cole’s media presence is extremely minimal. He’s hardly ever caught by the lens of the paparazzi. He rarely sits down for moments like these, and his social media footprint is just as minimal. He’s one of the more elusive members of the hip-hop elite, and one of the few rap stars whose stardom grows the more he limits his availability. So when he appears, it’s by design. And when he posts online, people pay attention.

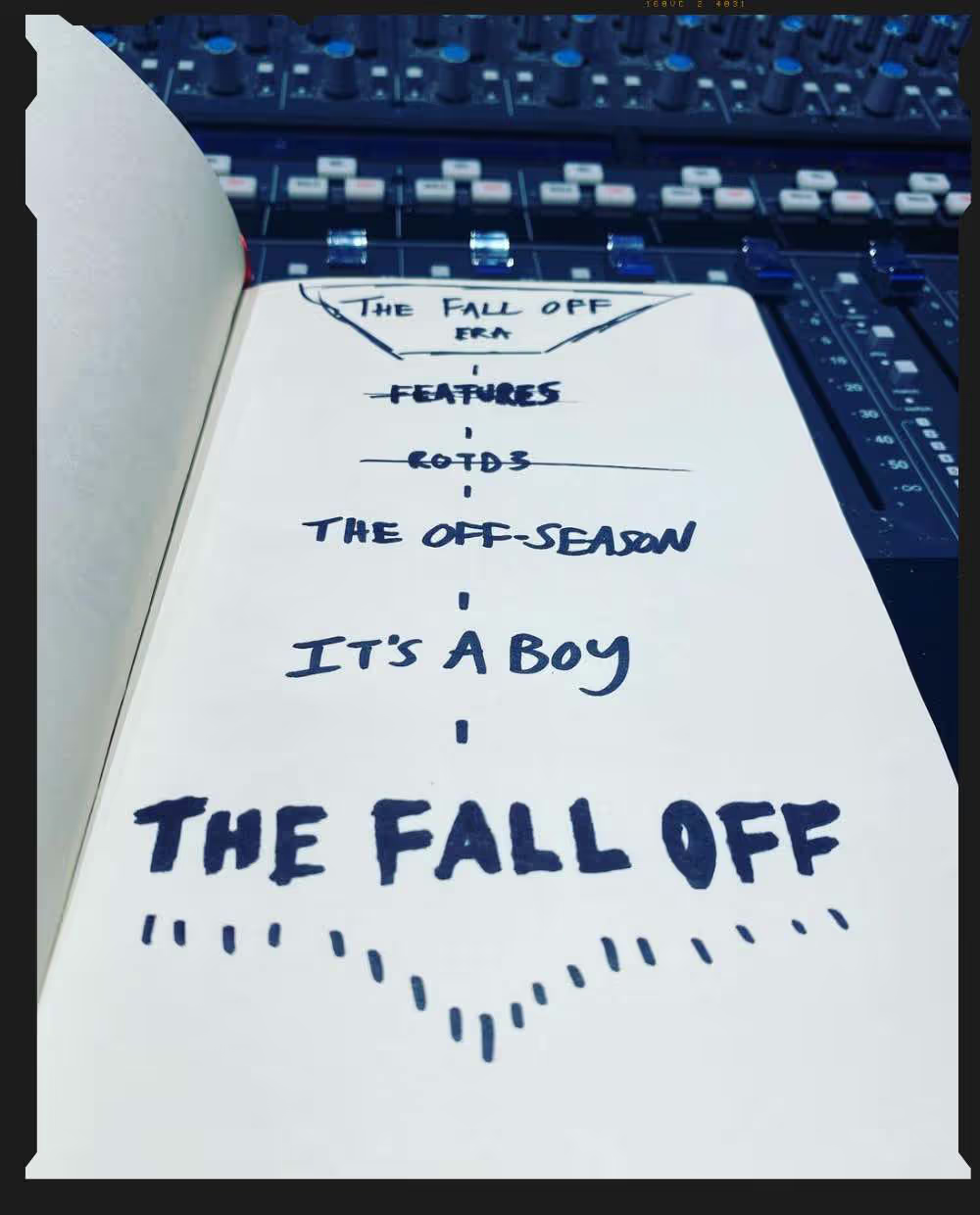

In the last days of 2020, sandwiched in between promotional posts for his signature sneakers from his PUMA partnership, J. Cole posted an image of a notepad resting on a studio mixing board.

The top of the page read: THE FALL OFF ERA. Beneath it, an ordered checklist with five items. The first two—Features (a reference to the run of guest verses J. Cole delivered to close out the last decade), ROTD3 (a reference to the Dreamville compilation album, Revenge Of The Dreamers III)—were struck through, symbolizing their completion.

The three remaining items on the page read: The Off-Season, It’s A Boy, The Fall Off.

Cole has previously described the first two as meaningful moments in his career centered around collaboration, both for the sake of creating valuable memories and for sharpening his skills. Which leads us to The Off-Season, Cole’s newest album. It marks the return of his basketball-themed projects, the latest since his debut major label album, 2011’s Cole World: The Sideline Story.

The title might suggest that it’s a project with relaxation at its core—a break from the big show. But for Cole, who treats rap like a full-contact sport and is perpetually at odds with comfort, he knows the true value of the phrase.

“The Off-Season symbolizes the work that it takes to get to the highest height. The Off-Season represents the many hours and months and years it took to get to top form.

“Just like in basketball, what you see him do in the court, that shit was worked on in the summertime. So for an athlete, if they take their career seriously and if they really got high goals and want to chase them, the offseason is where the magic really happens, where the ugly shit really happens, where the pain happens, the pushing yourself to uncomfortable limits,” Cole says, motioning his hands as if he’s wringing the sweat out of a towel.

It represents the practice, the training, the drills, the intensity, the craft. It represents pushing yourself. Even if all of the songs and the verses that were made during that time period can’t make The Off-Season, the project still embodies all of them.

Cole, now sounding like a coach, iterates, “Once you get to the season, it’s too late to get better. You’ll get better naturally, but what you know is what you know. You’re getting that shit off in the offseason. So that’s really what it represents. It represents the time spent getting better and pushing.”

Cole’s relationship with basketball isn’t one of just nostalgia or symbolism. He’s close to the game in the ways a rap star can be, like sitting courtside and dapping up LeBron at Lakers games, and even more rarefied spaces, like performing on the court during 2019’s NBA All-Star Weekend in Charlotte.

But it goes much deeper than that. Cole plays the game. Really plays.

He’s adopted a very consistent daily routine. “I work out in the morning, I do a basketball workout, I do my music, and then I do family time,” he says. “I wake up and I repeat. And I don’t do music on the weekend.”

Now, we’re not talking about just putting up a few shots here and there. “I’m working out for a reason,” he says. “I work out with intentions in mind.”

He uses a recent golf experience to explain how he approaches basketball. He recently hit the links for the first time in almost a decade. “First of all, my thought is, Oh, I see why people golf all the fucking time. This is amazing.

“And then my next thought goes, Damn, I want to get really good at this.

“And then my next thought goes, How good could I get? Like, Could I…?” Cole wonders aloud, allowing his voice to trail off, teasing the tone of possibility and curiosity. “That’s just how my mind works. It’s like, What’s the highest height I can climb?”

He approaches hooping similarly. “Basketball is the same thing. If the highest height that I can climb is rec league in North Carolina or in New York, where I’m averaging 20 points a game, like, All right, that’s the highest height I can climb. But I’ve got to max out! I got to get the most out of my body.”

Cole doesn’t know exactly where that basketball max out is. But he has every intention of finding out.

The rap x hoops Venn diagram I’ve been outlining might seem a little on the nose, but Cole states plainly that it’s how he made sense of the moment: “I look at this shit like basketball: You go to show up for a game, but you haven’t practiced in months. So, yeah, when you get to the game, you’re just not going to have the handle. You’re not going to be as creative because you don’t have the basics locked the fuck in.”

For Cole, this lapse in skill and the acknowledgement of its cause turned on a light bulb in his mind. “It was the first time that I became conscious of, like, Oh, this is where ni**as fall off. This is where it happens.”

The concept of “falling off” is a frightening one. The idea that you were once good or even great at something and now you are not. The notion that you are declining in the arena that you have worked so hard for. That the impact of your 10,000+ hours may be expiring. These compound when the work is inextricably linked to your person. When it’s the thing you love to do. When it’s how you make a living and foundational to how the world views you. And then there’s that question of Well, what should I do next? Again, for many people, it’s some scary shit.

When I float this concept to J. Cole, he adjusts himself in his seat. He’s sitting up, his eye contact intensified.

“Was there any fear associated with falling off?” I ask.

“No.”

Really?

“There’s no fear of falling off.” Adjusting again, this time from sitting up to leaning forward, Cole explains, “It’s an acceptance of the reality of what will happen when you decide to stop putting in the work. It’s just the inevitable result.”

Cole’s understanding of the decline in ability is different than how some think about it; it’s not linked to age the way it affects many athletes, or the way many of us assume it is in music. “In basketball, you have no choice, your body tells you when. You know what I mean? In this shit, I’ve got a choice. It was a decision. It was, If it happens, it’s because you allowed it to happen. Like, This is the point where it takes place, where the ni**as that you love, when it just didn’t hit the same. So you could fall victim to that right now and accept that and just keep either making music for the fuck of it, or just because it’s a business opportunity there, or you could really put in the hours and the months and the years it’s going to take to max out on your skill level and to max out on your ability so that when you look back you’re like, Damn, I really did check all the boxes. I really did push myself as hard as I could go.”

He’s brought me to that time after Forest Hills Drive, a time when his lack of inspiration revealed a crossroads.

“It was literally like looking at a fork in the road,” Cole says, moving his hands as if he were drawing up a play. “OK, you can go this way and continue to grow and get better, and push yourself and still feel feelings of exhilaration when you tap into new shit and move on. Or, you can go this way and live a more comfortable life that’s less inspired, less push, less stretching yourself and getting out of your comfort zone. So yeah, it wasn’t a fear, it was a decision.”

Cole chose to dream bigger. Climb higher. To not fall off.

This decision gained real estate in Cole’s mind over the next few years. As he continued to work, and push himself, he started laying down the groundwork. Building out a plan that would push him to grow as an artist. A blueprint of execution that would help to answer some of the internal dialogue and cement his decision to not decline.

“First it was the thought and the feeling, and I was looking for a phrase to sum that up. That was the birth of it,” Cole remembers. “I found the phrase in 2016, actually, early 2016 when I was working on 4 Your Eyez Only. I found a phrase, I did the hook to the song and I was like, Oh, this is the phrase that sums up this whole chapter for me. And that’s when I started working on The Fall Off.”

Part of the reason that Cole was able to channel what could have been an otherwise anxious chapter of his life was his connection with basketball and the way he parallels it to his career.

“You know why it don’t scare me? It’s because I’ve been through this before, it’s how I got on,” he says. “I know what got me here. I was lucky enough to be blessed with the first songs that I wrote. The first rhymes I wrote, I could tell, like, Oh, there’s a difference. I could see the difference between where I was at and where peers were at, and even people older than me. Then the first song I made, I could clearly see, like, Oh, something’s here.

“And even in college and shit, before I got the deal, I had songs like, ‘Lights Please.’ However, I remember a revelation, basically a feeling of, like, Yo, you have a great ability and you have some amazing songs right now. But you’re just sitting around as if that’s enough. Like, Oh, I got it. Oh, I’m about to get a deal because my music is so good and boom, boom, boom. And what it bred was comfort. It was a comfort in these songs that I had made and these verses that I had on tuck. A comfort in what I had already did, of like, Oh, this is going to get me there.

“And there was a revelation and it all stems from basketball. The thought was, Wait a minute, you sitting around broke, waiting on a record deal as if it’s just going to come. But let’s talk about basketball. You thought basketball was going to come. It was like, Well what happened with basketball?” Acting out both sides of the inner dialogue, Cole reveals, “Well, I thought I was nice, but the truth was I was working nowhere as hard as the people that were really about to get it. Because I didn’t know no better. So these dudes were really working every day and I’m playing. It’s like that childhood delusion, every kid think they going to make the NBA. I kept that shit for a long ass time. I kept that shit throughout my teenage years. As if, like, Oh, I’m just going to make the NBA, because I didn’t have the information to know, like, Ni**a, you’re not working hard enough.

“So once I have that realization, I’m like, Yo, now you’re 21. Do you really want to look back and say that the reason why you didn’t make it in rapping is because you didn’t put the work in? Like, Yeah, you got some songs. Yeah, you got some verses, but are you writing every day? Are you treating this shit like a sport?”

This was the moment that shifted everything. “That’s when my mentality switched. And, yo, that’s how The Warm Up was born. Every day I started writing verses, treating that shit like a sport. Like, Yo, I got to put up shots every day. Even if this verse never makes it, I’m just trying shit out in this verse. It’s just to get better and hone my craft. So when I did that, A, I noticed myself get even better, quicker. But now fast forward, now I have the tools to know that, like, Oh, this shit is just a sport. If you ever get rusty in rap, it’s because you’re not polishing. You’re not doing the work, you’re not practicing. You’re not putting the hours into your craft, because anybody can get sharp if you put the hours in.”

The path out of fear was through the work. And much like Kobe, he found strength in the challenge. And basketball became his totem, a talisman that he could associate with work and channel to find a path forward, even when inspiration or skill wasn’t readily available.

“The main parallel that I always draw between music and basketball is like, Yo, it’s just a matter of hours. The difference between the pro guy that sits on the bench and the superstar, it’s just a matter of intentional hours. They’re both really good, but that final foot of separation comes in the amount of hours that were put in. I think in order for any of those guys to be great, like LeBron, Steph, Damian Lillard, Kyrie, KD, there has to be an insane work ethic. You know what I mean? Especially looking at LeBron, the age he is. He has to commit way more to his body. You know what I mean? He has to do so much more than these other guys, just to stay ahead.”

The majority of our conversation about Cole’s past and present has a tone of preparation. There’s a focus and a constant perspective to what he’s saying, like he’s recounting the steps of a plan he’s been orchestrating for a while, continuing to check items off his list.

One of the moments he’s gearing up for is very clearly The Fall Off, rumored to be his final album. Cole has publicly floated the idea of his retirement dating back to at least 2016, despite sitting atop his field while simultaneously getting better and better at his craft. But there is an air of finality in our current conversation.

So I ask: It feels very much like you’re planning your 60-point game, and then walking off into the locker room and…

“Oh, bro, I’m super comfortable with the potential of being done with this shit. But I’m never going to say, Oh, this is my last album.”

You can’t.

“Yeah, exactly. Because I never know how I’m going to feel two years, three years, four years down the line, 10 years down the line, but please believe, I’m doing all this work for a reason.”

For him, it’s less about announcing a confirmed retirement and more about pushing himself. Making himself uncomfortable. Playing until the proverbial buzzer stops.

“I’m doing all this work to be at peace with, If I never did another album, I’m cool. That’s the reason for all of this, so I know that I put everything on the table. I left everything on the table, and I’m good with that. Because there’s a lot of shit I want to do with my life and in my life that, because I have such an intense love and passion for the craft, if I don’t let that go, I’m not going to be able to get to these other things that I also want to learn and grow and be good at.

“So it’s like, No, let me get everything out on this craft, to where I feel at peace. And then, guess what? If I’m inspired and I feel like doing it again, cool. But if not, I know I left it all on the table.”

Available now

Available now